This inscribed lintel forms part of a collection of Gandharan pieces at the Chau Chak Wing Museum [CCWM], University of Sydney. The Museum, which opened in 2020 brings together the University’s three main collections – the Macleay Museum of natural history, ethnography, historical photographs and scientific instruments, the Nicholson Museum of antiquities, and the University Art Gallery.

The CCWM lintel was donated along with sixty-four other cultural artefacts from Australia, Egypt, Greece and Pakistan to the then Nicholson Museum in 1994 by the Dutch businessman Herman Diederik Huyer, who settled in Australia in 1969. Huyer was born in the Netherlands in 1920, and after World War II worked for the Dutch multinational company, the Philips Group. He held posts around the world during his career, and from 1960-62 resided in Karachi, Pakistan. It was while living here that he acquired this particular piece from an art dealer in either Lahore or Taxila.

The scene in the CCWM lintel depicts the seated Buddha flanked by attendants. The Buddha is in a teaching posture with a nimbus behind him and tree branches extending around. The throne on which the Buddha sits is unadorned. There are three attendants on each side of the Buddha, two in front and the third is behind the front two. The four front seated attendants are monks and have similar stylistics features: seated, hands folded in their laps, robes having a thick fold around the neck, short hair, and elongated earlobes. The figure behind the monks to the right of the Buddha appears to be Vajrapani based on his wavy hair, lack of robe and that he holds a vajra (a thunderbolt scepter). The figure in the backrow on the left resembles the monks in the front row, however the fold of his robe around the neck is thicker and hangs lower than the other monks. The scene is bracketed by gandharan-corinthian columns on the sides of the lintel.

Based on these stylistic features the CCWM lintel appears to show the Buddha’s first sermon at Sarnath, referred to as the Setting in Motion of the Wheel of the Law (dharmacakrapravartana). Vajrapani, a yaksha who later becomes a bodhisattva, serves as a protector of the Buddha and the vajra, reconstituted from the Vedic god Indra, symbolises his power (Lamotte 2003). Vajrapani is a popular figure in Buddhist Gandharan art, possibly representing the “iconographical counterpart” of Ananda (Filigenzi 2007). A comparable lintel of the Buddha’s first sermon from Gandhara is found in the The Metropolitan Museum of Art (1980.527.4), and in this scene the distinction between Vajrapani and the monks is clear and the Buddha is holding the Wheel of the Law. In fact, events from the Buddha’s life, and previous lives contained in the Jatakas, were commonly depicted on sculptures affixed to the drum of Gandharan stupas. As Buddhists circumambulated stupas they would view these scenes of the Buddha’s life, much like one would read a book today.

The provenance of this piece is unclear. When Huyer donated this object to the Nicholson Museum he provided a short article about the history of this region and stated that he bought the lintel in “Taxila and Lahore in 1962”. Of these, Taxila would be the more probable find spot for the piece while Lahore would be the place of purchase. Taxila is located about 30 km west of Islamabad and was an important trading city in ancient Gandhara as well as a major Buddhist center. The most famous Buddhist stupa site in this city is the Dharmarajika stupa, which dates to the reign of the Mauryan King Ashoka, ca. 268-232 BCE. John Marshall and a team of archeologists extensively excavated Taxila from 1913-34 and discovered numerous stupa sites surrounding Taxila and unearthed a trove of Buddhist objects (Marshall 1951). It is likely that this lintel was found at one of the Buddhist sites at Taxila and was then acquired from an antiquities dealer in Lahore, but where and how Huyer acquired this piece is uncertain.

In addition to the carved relief, the lintel contains an inscription along its lower rim. However, after consulting with specialists in Gandharan epigraphy the inscription is most certainly a recent forgery. Some of the characters in the inscription resemble Kharoshthi and Brahmi letters, such as the up-curved head of a Kharoshthi kṣa and perhaps a Brahmi ya. However, other characters are incomprehensible and none of these individual letters represent a coherent line of text. The practice of adding an inscription to an object to increase its value is not uncommon in the art market, and this appears to be the case with this inscription.

A forged inscription does not mean that the entire object is a recent replica of Gandharan Buddhist art. The stylistic features of the CCWM lintel indicate this piece could date back to the early centuries of the Common Era when Buddhism flourished in Gandhara. However, in the 1960s there was a viable market for Gandharan Buddhist art and many artisans produced replicas around Taxila (Asif and Rico 2017). As it stands, the CCWM lintel sculpture appears to be authentic and is an exquisite representation of Gandharan art.

Keywords

Seated Buddha

Other References

-

Asif, Hassan and Trinidad Rico. 2017. “The Buddha Remains: Heritage Transactions in Taxila, Pakistan.” In The Making of Islamic Heritage, edited by Trinidad Rico, 109-22. Singapore: Plagrave Macmillan.

-

Filigenzi, Anna. 2007. “Ānanda and Vajrapāṇi in Gandhāran Art.” In Gandharan Buddhism: Archaeology, Art, and Texts, edited by Kurt Behrendt and Pia Brancaccio, 270-85. Vancouver: UBC Press.

-

Lamotte, Étienne. “Vajrapāṇi in India, part 1.” Translated by Sara Boin-Webb. Buddhist Studies Review 20.1 (2003): 1-30.

-

Lamotte, Étienne. “Vajrapāṇi in India, part 2.” Translated by Sara Boin-Webb. Buddhist Studies Review 20.2 (2003): 119-44.

-

Vajrapani Attends the Buddha at His First Sermon. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (1980527.4)

(

The Met

)

Digital publishing by Ian McCrabb, Yang Li and Isobel Andrews

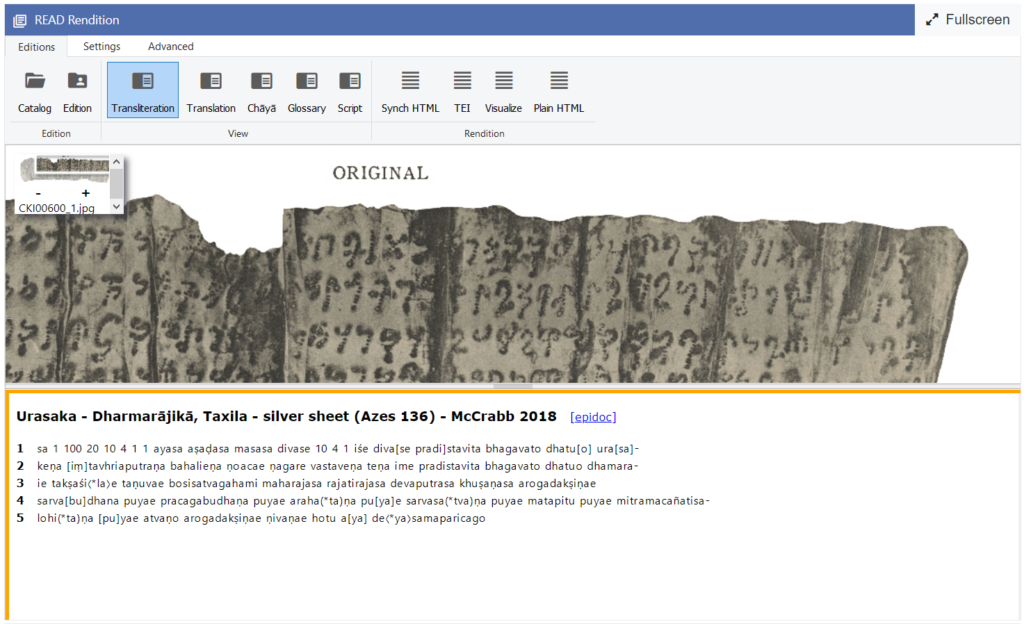

Each digital edition includes background information about the text, a summary of its content, and references to parallel texts and related publications. Users can explore the text, image, and other analysis resources through various preset views from the READ interface, or customize the views themselves.

By developing the text in READ, the text and image are linked such that selecting a syllable, word, or compound in the text or glossary will highlight the associated akṣaras on the manuscript. This allows you to in effect “read” the manuscript as you read the transcribed text, even if you do not know the script.

Users can choose from several preset READ views by selecting the tabs at the top. Each of these convenient arrangements of text and resources is suited to a different experience with the manuscript. For instance, choose the Script view to study the paleography of the manuscript or the Glossary view to study its vocabulary. It is recommended that the user toggles through the default views to gain a holistic perspective of the text.

- Transliteration: Image and transliteration.

- Translation: Transliteration and translation.

- Chāyā: Transliteration and chāyā.

- Glossary: Image, transliteration, and glossary.

- Script: Image, transliteration, and script chart

- Visualize: Visualize the text structure display.

- Synch HTML: Interactive synchronized rendition.

- TEI: EpiDoc TEI rendition.

- Plain HTML: Transliteration in HTML format.

Avś

Be

Ce

Ch.

CPS

DhG

Ee

FJJ

Mahīś

MūSā

Mvu

P

SĀ

SBhV

Se

Skt.

SN

T

Tib.

Vin

Avadānaśataka (ed. Speyer 1906–1909)

Burmese (Chaṭṭhasaṅgāyana) edition

Sri Lankan (Buddha Jayanti Tipiṭaka Series) edition

Chinese

Catuṣpariṣat-sūtra (ed. Waldschmidt 1952–1962)

Dharmaguptaka

European (Pali Text Society) edition

Fobenxing ji jing (T 190)

Mahīśāsaka

Mūlasarvāstivāda

Mahāvastu-avadāna (ed. Senart 1882–1897)

Pali

Saṃyukta-āgama (T 99)

Saṅghabhedavastu (ed. Gnoli 1977–1978)

Thai (King of Siam) edition

Sanskrit

Saṃyutta-nikāya

Taishō 大正 edition

Tibetan

Vinaya